Between 18 April and 22 July this year the National Portrait Gallery‘s travelling exhibition Inner Worlds: Portraits and Psychology will be held at the Ian Potter Museum of Art in Melbourne. It is accompanied by a marvellous website, developed for its first exhibition last year. Recordings of talks by several of the curators and a panel discussion which includes Sydney based psychoanalysts, Reg Hook and John McLean as well as Deborah McIntyre, formerly from Melbourne but now living and working in Canberra provides rounded commentary on the multiple lenses through which these portraits can be viewed. A portrait – and discussion with David Chalmers, renowned world-wide for his work on the philosophy of consciousness is also included, much to my delight. His edited text Philosophy of Mind formed the basis of a profoundly interesting, to me at least, online course on the philosophy of mind through Oxford University. Chalmers also has his own website which I urge you to explore, here.

Inner Worlds links portraiture with psychoanalysis in Australia during the twentieth century. It brings together portraits of the early psychologists and psychoanalysts to emerge in this country as well as work by artists who, responding to the ‘New Psychology’ became interested in the relationship between art, psychology, the unconscious and ‘intense mental states’. Much of this was undertaken between the two world wars of the twentieth centuryas experiences of war, trauma and the use of psychology in the treatment of those people who were severely traumatised by these experiences were becoming clearer. For this reason some of the ‘pioneers’ selected for this exhibition were from the medical field. John William Springthorpe and Paul Dane were Melbourne medical practitioners who enlisted during WW1. Their work and interest in psychoanalysis followed that of British – and German – colleagues who learned in the field that the ‘talking cure’ helped soldiers who were deeply traumatized by a battlefield like no other in human history. Indeed trauma, war neurosis, and hysterical paralysis were the significant subjects for inclusion in the British Medical Journal during these years. Another war veteran, Roy Coupland Winn, originally from Newcastle in New South Wales, and the son of the owner of Winn’s Emporium in that town, became the first Australian psychoanalyst to begin private practice – in Sydney.

Credit does need to be given to Melbourne based historian Joy Damousi for her excavation of this arena. Her research, published in her 2005 book, Freud in the Antipodes, informs this exhibition – although those who are designated pioneers are as interesting as those who are omitted. Psychologist and Educator, Tasman Lovell, appointed Professor of Psychology at the University of Sydney in 1929 is generally credited with developing the first separate department of psychology in Australia in 1939. Not included is his counterpart, Philip Le Couteur, appointed Professor of Moral Philosophy at the newly opened University of Western Australia in 1913. Both were appointed in the war years during which they developed courses in experimental psychology and which included psychoanalysis by 1918. Australia was a small place then. Psychology was presented as a branch of philosophy. Le Couteur did not stay in Western Australia, however. Family concerns in the eastern states resulted in his decision to resign his post and move to Melbourne where he took up the headmastership of Methodist Ladies College by the end of 1918.

Representing the clergy is Ernest Burgmann, appointed the Anglican Bishop of Canberra and Goulburn in 1934. Generally credited for his social activism, as Damousi notes, Burgmann sought to marry this with his religious committment. His interest in psychoanalysis appears to have begun in the 1920s when he attended Tasman Lovell’s lectures at the University of Sydney. By 1929 he was writing of its applicability to disciplines – anthropology, criminology, education, theology, economics and literature. It is hard to guage on the amount of evidence provided whether Burgmann’s interest was a consequence of his own particular questing mind. He appears to have been a person of many interests. Nevertheless Burgmann, the theologian and clergyman was not alone in his appreciation of the usefulness of psychoanalytic thinking in this line of work. He was not necessarily a pioneer, though. In 1923 Congregational minister Nicholas Cocks had written at length about the congruence between the psychoanalytic process and the theologians work in an article published the second edition of the Australasian Journal of Psychology and Philosophy. Unfortunately Cocks died suddenly in 1925 – too early, really. Perhaps there are other contenders for the pioneering label. There is till much more to explore in the Australian field.

Of course the early psychoanalysts are central to this exhibition which includes portraits of Clara Geroe, the first training analyst in Australia by Judy Cassab.

Clara Lazar Geroe together with her husband and child and her colleague, Andrew Peto with his wife, arrived from Europe and Nazi persecution during 1940 – after protracted lobbying from British psychoanalyst Ernest Jones. He had also had ensured Freud was released from Germany – despite the reluctance of the British Government to act on the refugee issue. Instrumental for her acceptance as an emigrant was the advocacy of the Australian psychiatrists Paul Dane, Reg Ellery, Coupland Winn, along with the clergy through Bishop Burgmann, and head of the Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sir Charles Moses. This group had taken their case to the Australian Department of Interior. Geroe, a trained analyst and member of the The Budapest Psychoanalytical Society, subsequently became Australia’s first Training Analyst and a founding member of the Australian Psychoanalytical Society in Melbourne.

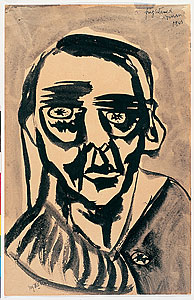

Dr Clara Geroe – by Judy Cassab

In 1982, Geroe’s interview with by researcher, Douglas Kirsner was published in the Melbourne journal, Meanjin, then under the editorship of Judith Brett in September 1982. Here Geroe related that her first contact with psychoanalysis occurred when she was taken by her older sisters to a talk given by psychoanalyst Salvador Ferenczi a doctor in the hussar regiment garrisoned in her home-town in Hungary during WW1. His book on psychoanalysis, available in the local bookshop, was purchased by her parents. She told Kirsner,

I secretly pinched it, read it and said, ‘Oh. This is what I want to do’. I was then in the middle of my high school years and I somehow knew I must not study it yet or I would never go through with my planned medical studies.

Geroe successfully completed her studies and became a member of the Hungarian Psychoanalytical Society. But by the mid 1930s it was clear that the Jews were under considerable pressure to evacuate Europe.It was becoming clear to Jewish people that Hitler’s regime was no longer willing to tolerate their presence. At the International Psychoanalytic Conference in Paris during 1938 Geroe began exploring the possibility of herself, and five other analysts migrating to New Zealand. However few countries, including New Zealand and Australia, were willing to consider, if at all, taking refugees beyond quotas established in the 1920s. The Evian Conference called by US President Roosevelt had done little to change this. The New Zealand government refused the applications of all six. In Australia Geroe was accepted because, she reckoned, she had a child. It is not clear whether Andrew Peto was one of the six. Refugees were not welcome anywhere, it seems.

From her arrival in late 1940 Geroe was was a central figure in the development of the field and the training of psychoanalysts in Australia. She was instrumental in the beginning of Melbourne’s Children’s Court Clinic and the Koorong School run by Janet and Clive Neild in Melbourne. Western Australian born psychoanalyst Ivy Bennett who practised in Perth during the 1950s remembered the warmth of Geroe’s welcome and her encouragement – ‘before the Graham controversies’ began in the late 1950s – perhaps an allusion to the nascent Kleinian influence which in the 1960s. Andrew Peto did not fare as well. After some years battling the authorities over his qualifications he left Australia for New York where he established his practice and gained recognition. Indeed a little internet search finds him as having delivered the 1978 Brill Memorial Lecture on the subject: Rondanini Pieta: Michelangelo’s Infantile Neurosis’.

In his 2002 book, The Hitler Emigres, a study of the contribution of Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany on British culture, historian Daniel Snowman notes that Jewish people were denied entry to a number of the professions. Instead many gained their education in the arts – literature, music, art – deeply educated in these fields. Geroe told Kirsner in 1982:

It is hardly necessary to say that members of the Society were all extremely cultured. Analysis was a cultural and vocational interest and not very lucrative. You had to be a bit of a revolutionary to become interested, to think for yourself and not be with the establishment. Amongst ourselves there was no distinction between medical and non medical people, and nowhere were women treated more equally than in analytic circles. I became very interested in child analysis and worked with Alice Balint in a children’s clinic. Unfortunately it was closed down when the Nazis came. Child analysis was beginning; Melanie Klein had begun working and Anna Freud had written her first book. We had very intimate contact withj Anna Freud and her group; child analysts met weekly in Budapest and Vienna and we would sometimes go on an exchange seminar to Vienna for the weekend.

During the 1940s, the work of these analysts, developments in training and clinical experience, reached the consciousness of artists such as Joy Hester and Albert Tucker.

(Joy Hester – 1945: Frightened Woman).

Both artists responded to the traumas of war – representing the internal agony experienced by many returned soldier, prisoners of war and holocaust survivors – men and women in their art work. Some of Tucker’s series, Images of Modern Evil is captured here.

This exhibition is about ‘sight and insight’ – It is about looking and beginning to see and to think about what might be happening in the minds of oneself and another beneath the surface appearances. it is about learning that intense emotional experiences and mental states can be thought about, talked about in a number of ways: though words, painting music and other forms. Perhaps it is also a plea for the value of the humanities and culture – so often decried these days in the academy – but which in themselves are about the attempt to understand human experience.

The advent of the the National Library’s online digitised newspapers collection enables this historical record to be easily mined – and the discovery that there was widespread interest in this field beyond cities, intellectual elite and artists – in places as far afield, and remote, as were Rockhampton and Cairns in far North Queensland, Broken Hill in far west New South Wales and Kalgoorlie a gold mining town in Western Australia. That said, a search through the newspapers of all the major capital cities may well have yielded results for the historian Joy Damousi, whose book Freud in the Antipodes has also structured this exhibition. I would have liked to see a more representative group of pioneers – from across the country – whose advocacy for understanding the inner world did not find its time. That Bill McCrae sought the support of the British Medical Association in an attempt to establish a psychoanalytic institute at the University of Western Australia in 1943 is missed; that several very talented women – including Ivy Bennett and Ruth Thomas, both from that state, found their way to London and psychoanalytic training with Anna Freud’s group has also been missed. Thomas ane Bennett had in common their experience with the educationalist Professor Robert Cameron at the University of Western Australia during the 1930s and 1940s.

Of course one cannot have everything. It is enough to know that with this exhibition which is touring Australia during the next couple of years, has opened the door to an essential moment in Australian cultural history.

Leave a comment